Sudhir Patwardhan’s art has always centred Mumbai’s working class.

| Photo Credit: Emmanual Yogini

Giant arcs of metal and concrete dominate the landscape. Skyscrapers with sea views have balcony seats to the excavation of Mumbai’s soul. As three figures from the Holocaust gaze silently into the city’s bowels where a grave of bodies lies forgotten and surrounded by demolished homes, a red wave on a highway leads cars to a gate on the upper right corner of the painting: the doorway to Auschwitz. ‘Work liberates’, the Nazis had emblazoned on the concentration camp gate.

At least a million people were exterminated here, many forced to labour until they were murdered. Artist Sudhir Patwardhan wants you to think about the purpose of ‘development’. He says it’s also a statement on the “absurdity of a nation which was created because of the suffering its people had undergone during World War II, and now they have become the perpetrators of another kind of Holocaust against another community… we repeat history in so many ways.” He is talking about the war on Gaza.

For 50 years, Patwardhan’s art has centred Mumbai’s working class. For three of these decades, he had a day job as a radiologist (he started painting in medical school), until his art finally started providing a livelihood. Now 76, he looks more bespectacled radiologist than artist. He says his new work reflects “some negativity” about the city he has been “attached to for a long time”.

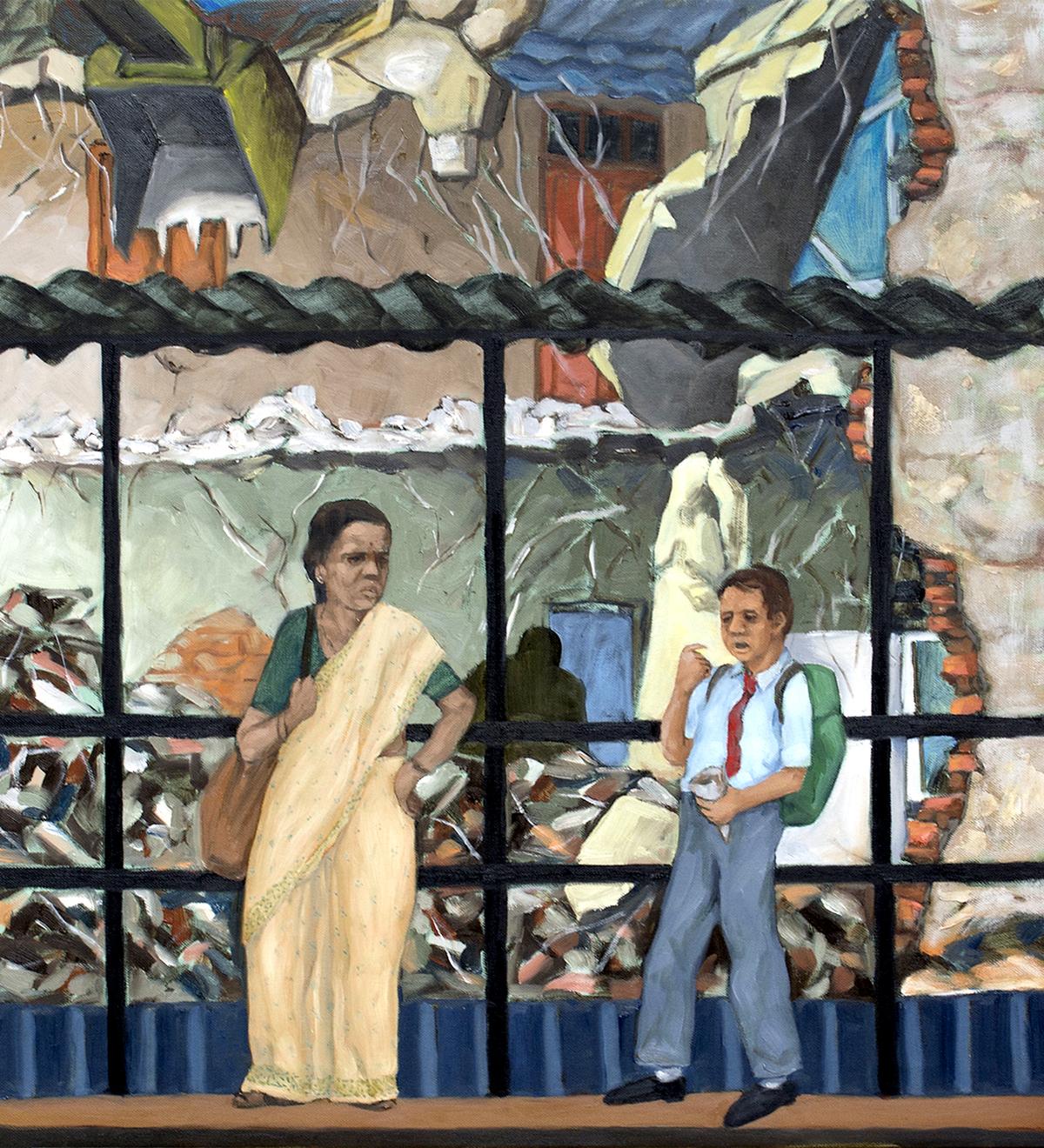

‘Built and Broken’ by Sudhir Patwardhan

The Thane-based artist’s post-pandemic works highlight the exclusionary nature of development. For the labouring classes at least, the idea of city as urban utopia has crash-landed. “Somewhere in the future, maybe the city will be a better place, a different place, but it’s bound to be that only for a certain class of people,” says Patwardhan, whose travelling exhibition Cities: Built, Broken showed in New Delhi and Mumbai recently, and will pause next in Kolkata and Kochi.

“In the last couple of years, one has become exposed to what is happening all around the world, where cities can be wiped out,” Patwardhan says. “The whole idea of ‘cities’ itself seems purely about real estate. Donald Trump, for example, sees Gaza as real estate.” He’s referring to the U.S. President’s desire to turn Gaza into the ‘Riviera’ of the Middle East. “The absurdity of today’s life is overpowering,” he adds.

A city changed

Patwardhan’s figures have always looked pensive, now they are weary, defeated, disconnected. If his famous 1977 Irani Cafe depicted a robust gent in a crisp kurta sitting at a marble-topped table, in his new painting of an Irani cafe, the central figure is skeletal and raggedly dressed, mirroring the turmoil in the land he migrated to and the one from where his ancestors came. ‘Is shahar mein har shaks pareshaan sa kyun hai?’ (‘Why does everybody in this city look worried’), a visitor to his Mumbai show quoted this line from an Urdu ghazal by Shahryar, Patwardhan tells me, with a laugh.

‘Bus Stop’ by Sudhir Patwardhan

The artist and his wife Shanta Kallianpurkar show up together every day at the Mumbai gallery, greeting old friends and visitors who throng the exhibition. Down the road, a retrospective of Patwardhan’s best friend Gieve Patel, who passed away from pancreatic cancer in 2023, is showing.

The two first connected when art critic Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni suggested Patwardhan meet the “other doctor who is a painter”. It was the start of a friendship that included critiquing each other’s work. On display at Patel’s show is Patwardhan’s painting of the two friends deep in conversation at Marine Drive, their regular adda. There’s another work by him too, of Patel’s last week in the hospital. Patel is dressed in white pyjamas and kurta and is sitting on a bed. There is no fear or regret on his face, it’s a portrait of a man ready for whatever comes next. A well by his side depicts a childhood fascination of Patel’s. Patwardhan worked all night to complete the painting from a photograph he took of Patel, but his friend was unimpressed. He said his left arm was not visible, so Patwardhan painted it in.

Space is political

Sudhir Patwardhan’s ‘Under a Clear Blue Sky’

From the socialist 1970s to the ‘super development’ of this age, Patwardhan’s eye has always been empathetic and from the point of view of “ordinary people living through this period”. His words may be gently understated, but his paintings tell another story. Demolitions are everywhere. A Muslim man, his back to the viewer, watches as a yellow JCB demolishes his home. Patwardhan feels acute discomfort about the “bulldozer Raj” and how it has become “less and less possible for people to speak out about anything”. Other visible influences include the increased overcrowding and militarisation of our cities; clamping down on artistic freedoms; the geography of societal divisions; and the violence on television and in real life. “Hopefully people wake up to this reality and try to change things,” he says.

In another painting that depicts a thrumming collage of city dwellers, he starts with a central sketch of an Ajanta Caves gate that takes him on a journey through December 6, Ambedkar’s death anniversary, and Buddhism. “Like the Marxist thinker Lefebvre, Patwardhan’s intent is to show that space is political, even as it demonstrates a derailed modernity project,” writes art critic Gayatri Sinha in the show’s catalogue.

Or in Patwardhan’s simpler words: “The life of people who endure through this must be recorded and must be spoken about.” That’s exactly what he has done for half a century and why he has such a large following.

The writer is a Bengaluru-based journalist and the co-founder of India Love Project on Instagram.

Published – April 10, 2025 04:33 pm IST