Across the globe, storytelling is being reimagined. The lines defining who gets to create art and tell a compelling story are also blurring. Museums, especially, are figuring out how to better tell the stories of their land. In Australia, Melbourne’s Bunjilaka Aboriginal Cultural Centre sensitively portrays the history and traditions of the Aboriginal communities through performance, storytelling, artwork and audio-visual interventions.

In Lisbon, Quake: The Lisbon Earthquake museum allows visitors to travel back to 1755 to relive one of the city’s most transformative events. Over an hour-and-a-half, and 10 immersive rooms, audiences can hear, smell, and feel the heat from burning buildings. In Germany, Stuttgart’s Art Museum has incorporated AI-infused storytelling. And in the U.S., New York City’s Museum of Modern Art has its Oral History initiative — a way to preserve first-hand recollections of individuals in their own voice.

Closer home, museums and artists are experimenting, too.

Parvathi Nayar’s ‘Limits of Change’

In Chennai, the artist’s Limits of Change is a project built of theatre, installation, art, and more, or as Parvathi calls it, a ‘story museum’. She and her playwright niece Nayantara Nayar had the idea to marry the concept of museums with performance. Parallelly, they were also inspired by the shifts in theatre, where dramas unfolded through headphones on a city walk with actors or within a miniature set. From this confluence — where archives, performance, and interactivity intersect — the ‘story museum’ emerged.

“Nayantara and I came to it as a space where historical fictions can activate our lived histories, where stories are experienced through art installations and infographics, and brought to life by movement, spoken word and text,” she explains. “Creativity, after all, comes from allowing ideas to jostle, percolate, and fuse, until something entirely new takes form.”

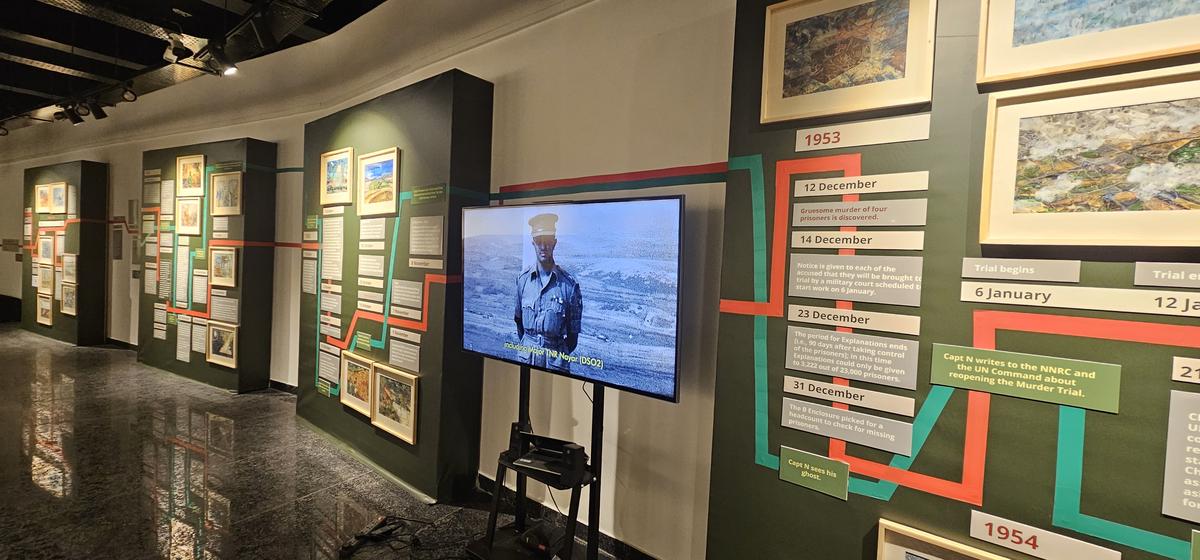

The timeline

Guests in the Arrival Room, tying peace ribbons

Parvathi’s father, Major General T.N.R. Nayar, was part of the Custodian Force of India (CFI) and was sent to Korea on a peacekeeping mission following the signing of the Armistice of the Korean War in 1953. Years later, with the help of letters and journals he left behind, Parvathi and Nayantara took the audience on a journey with the Indian soldiers who spent nearly a year in the Korean Demilitarized Zone. The narrator was a young curator and through nine interconnected spaces, each representing a part of the DMZ, she and her assistant narrated the story through exhibits, archival footage, theatrical performances and the like. In a sense, they created a museum with a fictional story as its soul. It is looking to travel across India and Korea.

MIss P and the Princess of Ay

Court Martial Room

The inspiration came broadly from projects and installations the duo had seen in museums in India and abroad. Nayantara was also inspired by the U.K.-based theatre company, Paper Birds’ show Mobile — a product of time spent with communities, listening to personal experiences, and using people’s words to paint powerful social commentaries.

Tasneem Mehta at Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum

Mumbai’s oldest museum routinely activates its collections by transforming static displays into immersive, evolving experiences. In its own way, it merges stories with the museum’s exhibits. Mehta, the curator, has invited prominent multi-disciplinary artists to engage with the collection to deconstruct, decolonise, and challenge the ways of looking at the world. Conceptual artist L.N. Tallur’s Quintessential used Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity as a starting point to explain his universe. Visitors loved participating, and switching on and off the mechanical exhibits.

L.N. Tallur’s Quintessential

| Photo Credit:

Anil Rane

Atul Dodiya’s 7000 Museums: A Project for the Republic of India

| Photo Credit:

Anil Rane

“I didn’t want to do it in a didactic way, so it is done by inviting artists to create their own narratives and ways of engaging with the material,” says Mehta. Several artists, including Nikhil Chopra, Sudarshan Shetty, and Sarnath Banerjee, have engaged with the museum.

Nikhil Chopra: Yog Raj Chitrakar – Memory Drawing X, Part I and II

Even the current exhibit, Cartographies of the Unseen by artist Reena Saini Kallat, is a product of this. Mehta worked closely with Kallat to decide where her artwork would be placed around the colonial museum. It was a way to challenge the European point of view. “A lot of thought went into where I placed the crown on which the names of freedom fighters are engraved or [why we] placed the Constitution in front of the statue of Prince Albert,” Mehta adds.

Karthik Subramanian’s story exhibition

For the Auroville-based photographer and multi-disciplinary artist, telling stories is part of his art. For his exhibit Sleepwalker Archives at the French Institute of Pondicherry last year, Subramanian and his colleagues had access to archival photographs, herbarium specimens, card catalogues, maps, instruments, and a range of miscellanea from the institute’s archives. In the process of sifting through the material, they explored the possibilities of animating connections between the objects and the worlds contained in them — reading them in a spirit of play.

“Every time I go to an exhibition, I find myself desiring to touch many of the objects on display. “So, in our show, what we wanted to bring to the viewer was the feeling of embodiment — with all of one’s senses,” says Subramanian. “Can one listen to, smell or taste a photograph? Can one feel the movement in a still photograph? Can we make the viewers imagine what is outside of the frame?”

Sleepwalker Archives

He believes that the subcontinent has its fair share of oral stories, poems, and epics that are excellent carriers of history and knowledge. “I find the older South Indian temples to be a museum, where visitors engage all of their senses to immerse themselves into one particular story or several stories held together in that space,” he explains. “This, I believe, allows them enough room to bring their own reading and interpretation of the narrative, story or historical event — as we collectively keep reading, re-reading and retelling and rewriting the stories over and over.”

The writer and journalist is based in Chennai.

Published – April 17, 2025 04:16 pm IST